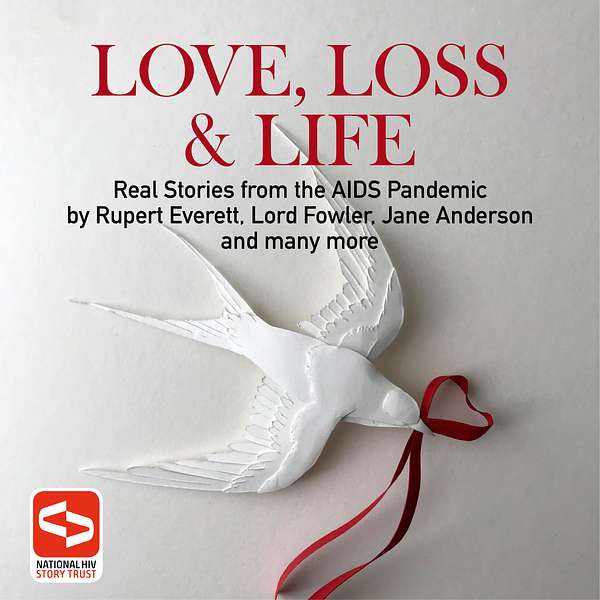

Love, Loss & Life: Real Stories From The AIDS Pandemic

Introduced by Anita Dobson and voiced by actors Christopher Ashman, Elexi Walker, and Kay Eluvian, the series features stories taken from NHST’s first book, a collection of essays, reflections, and testimonies also entitled ‘Love, Loss & Life’ which was published in 2021. The book and podcast series feature in short-form just some of the moving and tragic recollections that the NHST archive of over 100 filmed interviews, currently housed at the London Metropolitan Archive, capture in expansive detail. This extensive archive provides a 360-degree thought-provoking view of the AIDS pandemic in Britain through the real-life experiences of those who were there. Since 2015, over 120 interviews have been filmed with survivors, family members, friends, advocates, and medical professionals candidly remembering their personal experiences. Through archiving these films at the LMA, and sharing the stories collected through education, media, and art projects, NHST’s mission is to preserve the story the HIV and AIDS pandemic for those who know it, and to teach it for the first time to those who do not.

Love, Loss & Life: Real Stories From The AIDS Pandemic

Love, Loss & Life: Real Stories from the AIDS Pandemic: Flick Thorley

Your feedback means a great deal to us. Please text us your thoughts by clicking on this link.

In the early years of the AIDS pandemic, the focus was on the physical needs of people with the illness. But by the 1990s it was becoming clear that people with AIDS could also become acutely psychiatrically unwell, often as a result of the illness attacking the brain, and that the NHS didn’t have the facilities to cope with this aspect of the condition. Flick Thorley recalls the pioneering work she was involved with at that time which helped remedy the situation, and the care given by the London Lighthouse.

This podcast series features stories taken from our first book, a collection of essays, reflections, and testimonies also entitled ‘Love, Loss & Life’ which you can buy here.

An audiobook is also available here.

Visit the National HIV Story Trust website

Love, Loss and Life. Real stories from the AIDS pandemic. This is Flick Thorley's story, read by Elexi Walker with an introduction by Anita Dobson.

Anita Dobson:Flick Thorley was born in New Zealand and trained there as a nurse in the mid 1980s. She came to the UK in 1989 and began working as a psychiatric nurse at University College Hospital, UCH, in London. She became a charge nurse at the London Lighthouse, and later worked on the HIV ward at the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, where she was also instrumental in setting up a club drugs clinic. She and her partner Chloe Orkin, a consultant, also working in the field of HIV and AIDS were seconded to Botswana to set up an antiretroviral programme there for HIV sufferers. Flick has retired from the NHS, but now volunteers with her dogs offering pet therapy in hospices.

Elexi Walker:In the early years of the AIDS pandemic, the focus was on the physical needs of people with the illness. But by the 1990s, it was becoming clear that people with AIDS could also become acutely psychiatrically unwell, often as a result of the illness attacking the brain, and that the NHS didn't have the facilities to cope with this aspect of the condition. Flik Thorley recalls the pioneering work she was involved with at that time, which helped remedy the situation and the care given by the London Lighthouse. As a psychiatric nurse, the first person I looked after who was HIV positive, was a young boy with psychosis in a psychiatric hospital in New Zealand. And it wask, to put it mildly, a disaster. We were scared of it and scared of him. I feel ashamed looking back of how we treated him, because he was just a frightened ill kid whom we kept in an isolation room and barrier nursed, double gloved. double gound. His cutlery was plastic.. he ate off paper plates, and we burned his bedding. Even then, I realised that the way he was treated was unacceptable. But at the time, we just didn't know how to handle this terrifying illness. By the early 1990s, I was a nurse on one of the acute psychiatric wards at UCH in London. A young gay man with advanced HIV was transferred to us because the HIV ward at the Middlesex could no longer cope with him. He was psychotic and demented with brain lesions caused by HIV. And he was dying. We couldn't cope either. Because we weren't set up to deal with the physical side of his illness, such as uncontrollable diarrhoea. Here I was, again, trying to nurse someone in a completely inappropriate setting for their condition. Because there was no appropriate place. He couldn't be at home safely. He couldn't be on a medical ward safely. He couldn't be in a psychiatric hospital safely. And he didn't know where he was. But he knew he didn't want to be there. The upshot was that he was moved back to the Middlesex and I became a liaison nurse between the HIV ward there and the psychiatric ward at UCH so that his psychological needs could be met, as well as his physical ones. We were if you like writing the book as we went along, but it was about treating people with respect and dignity, seeing the person as the primary point of care. The fascinating aspect of HIV care for me is how much it was led by activism. Gay men who were outraged by what was happening, and how they were victimised and demonised who shouted from the rooftops and demanded that the NHS and the drug companies took notice. Many of my nursing colleagues, male and female, were gay themselves, as am I. And this helped drive through change quickly. It was a remarkable milestone in health care, and it changed the way we conduct palliative care. I would argue that funding cuts notwithstanding, the legacy of HIV is its revolutionary and lasting impact on our health service. I began working at the London Lighthouse in 1994. I loved the place. A sympathetic setting where both physical and mental needs could be met. I was a charge nurse on the residential unit, dealing with people who presented with a broad spectrum of physiological problems, from understandable anxiety or depression about their situation through to HIV related dementia and other psychosis. Some came in for regular respite to give carers a break. Some needed a period of convalescence after hospital, and some were there because they were dying and needed as good a death as possible. I feel privileged to have sat at their request with dozens as they died, helping them feel safe enough to let go. The thought of some of those people still makes me cry. Every time someone died, we would light a candle on the main reception desk with a card by it with the person's name. You would know when you came into work to start your shift whether someone had been caring for a died overnight. It's a tradition I keep even now. And although I'm an atheist, I always open a window to let the persons spirit out, because when you are with someone as they die, you can feel that moment of transition. There was a mortuary at the Lighthouse, so that families and friends could stay last farewells if they hadn't been there at the end. Some were still reeling from only discovering their son or brother was gay when they learned his diagnosis, and then that he was dying. Some families were wonderful, at the bedside for week after week until the end. We would be invited to funerals, but I rarely went. There were just too many to go to. We encouraged people to make living wills, which would not only cover how they wanted to be treated in their last hours, but also whom to call. I vividly remember one young man who had been outed as a very young teenager and thrown out of the family home by homophobic parents. In order to survive, he became a rent boy. He was still only in his early 20s when we sat down with him to make his living well. He told us that under no circumstances, even if he no longer understood what was happening to him, should we call his mother. Towards the end of his life, he developed dementia. As he lay dying, he began to cry for his mother and begged us to call her. He had no recollection at all of the last 15 years, and the catastrophic row with his parents. He was terribly distressed. So we were faced with the dilemma. The Living Will was to us a morally binding document. He had been adamant before dementia set in that we should not call his mother whatever happened. Yet now, he was a child again, desperate for her comfort. From everything he had told us, we were sure she wouldn't come. We consulted his friends and decided we should try to find his mother. It turned out she was wracked with guilt and distress about how she treated him. And she came to see him and hold him one last time before he died. It had been the right thing to do. Though for some families, the rifts were irreconcilable. When a couple of years later, protease inhibitors like Ritonavir came on stream. I'm embarrassed to say I didn't hold out much hope. The side effects were horrendous. And many people were already too sick to gain any benefit. Some, like Efavirenz, even added to their mental health problems because they cause sleep disturbance and horrific nightmares, indistinguishable from reality. But over the next few years, we began seeing a real change. Suddenly, people were living with HIV. There were still hospitalizations. But people weren't dying in the numbers they had before. The residential unit at The Lighthouse closed because there was no longer a need for it. And I moved to a new job at the Kobler Clinic at the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital. Mental health care was as important as ever for HIV patients. Some had lived so long in the expectation they were going to die, that they now couldn't cope with surviving. They might feel guilt that antiretrovirals saved them, but had come too late to save a beloved friend or partner. Others got into trouble because they had incurred massive debts in the expectation they would not be around when the bailiffs came to call, but now they had to pay it all back. Some couldn't work out if they wanted to live or die, and began playing Russian roulette with their medication, stuffing it for weeks at a time, then frantically going back to it. The Apocalypse that had decimated social networks for so many gay people took its toll. There were issues with alcohol and party drugs, and a growing crystal meth problem associated with the gay scene where people got so out of their heads, they were incapable of practising safe sex, regardless of their HIV status, not to mention the associated paranoia and psychosis. The club drugs clinic I was instrumental in setting up was geared to specifically address those issues around sexual behaviour, chem sex and the gay scene. I wish I could say everything is fine now. But people still die from AIDS, mostly those diagnosed late. There is still ignorance and prejudice about HIV. Not so long ago, I was chatting to a nurse who asked where I used to work. When I said I had looked after HIV patients for a large part of my working life, she was stunned. Really, all that time and you never caught it. I thought back to how I tried to impress upon colleagues, the importance of universal hygiene and precautions, whoever you look after. The person you know to be HIV positive, is much less risk to you than the person who hasn't told you or who doesn't know themselves. We need to tell these histories to a new generation, reminding them that although we have treatments, we still don't have a cure for HIV and AIDS.

Unknown:Thank you for listening to this story from Love, Loss and Life, a collection of stories reflecting on 40 years of the AIDS pandemic in the 80s and 90s. To find out more about the National HIV Story Trust, visit nhst.org.uk. The moral rights of the author has been asserted. Text Copyright NHST 2021. Production Copyright, NHST 2022